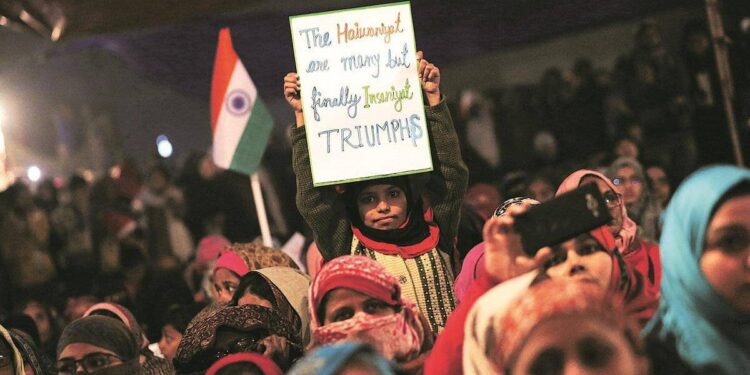

A file photo of protesters at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi Express photo

A file photo of protesters at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi Express photoThis is a very confusing book. From the name of the author and the title it seems it is a commentary on current times when most intellectuals belonging to what is called the Left-Liberal category, which includes Thapar, categorically believe that we are slipping into an authoritarian state where a mere dissent on any issue is enough to get one labelled anti-national. One can agree or disagree with this description, but the main requirement is that the votaries of either camp should build their case with sound historical surveys. This survey can begin from various points in history—ancient, medieval, modern—but the bulk of the analysis should be in picking up instances from contemporary times and comparing or contrasting them with other periods of history.

It is quite well known that Thapar is a renowned historian and has a distaste for the BJP and its ideology and politics. So, if a book or an essay bearing her name appears with a title, Voices of Dissent, one is led to understand that it would analyse current times with other periods of history and build a case of the state turning authoritarian and majoritarian and how it never was of such nature in the past. Since Thapar is a historian of ancient India and much of her work is restricted to that period, the reader would anticipate how well such a scholar has dealt in analysing the current times.

However, anyone attempting to pick up the book with the above mentioned expectations would be hugely disappointed. The bulk of the book deals with the ancient period and there, too, with the way religion and religious practices evolved with dissent playing a key role, something which children study in school. The analysis relating to contemporary times is sketchy and has a broad commentary on British policy of divide and rule, diatribe against hindutva, and extolling the Shaheen Bagh congregation.

Thapar has defined dissent broadly as disagreement with whatever was the mainstream and in pre-modern times analysed it in terms of dominant religions of the period and how various groups or individuals disagreed with the dominant creed, which led to emergence of several other religious sects or groups. So, in a way orthodoxy led to heterodoxy and pluralism was the buzzword and accommodation the dominant practice. Vedic Hinduism or Brahminism led to religious sects like Buddhism, Jainism, much later Sikhism and even cults like Bhakti and Sufism. While Hinduism was never monotheistic and practices varied with time and region, even Abrahamic and monotheistic religion like Islam had pluralistic shades with practices like sufism. Muslims may have a different religion in India but their practices were similar to Hindus within a region so there was nothing like pan-Islam.

For instance, a Muslim of Bihar has more in common with a Hindu of Bihar than a Muslim of Kerala. Building on this, Thapar says there was no such thing as fixed religion but what abounded were sects and regional practices.

Everything got destroyed with the coming of the British who did not understand these Indian practices and for purposes of their administrative convenience and political shrewdness, categorised Hindus and Muslims into fixed religious categories. This led to Hindu-Muslim politics. The narrative then abruptly jumps to Gandhi’s Satyagraha and trying to find its tradition in Indian history, and then quickly jumps to celebrating Shaheen Bagh and its demonstrators as perfect dissenters with whom the government should have engaged to keep intact our glorious tradition of celebrating dissent.

As with her history, Thapar is selective in her analysis too. There’s no analysis of the troubled aspects of Hindu-Muslim history like temple destruction, etc. She mentions some cases prior to Muslim rule where Hindu kings conquered neighbouring territories and destroyed temples. However, she completely ignores the fact that in such temple destruction by Hindu kings the idols were never smashed but brought back by the victors to their kingdom for adorning in their temples. Quite in contrast, the Muslim rulers while demolishing temples even smashed the idols.

Thapar highlights that there was harmony between Hindu and Muslims before the British came, but omits the fact that there were instances of discord also.

The Hindu-Muslim story is basically of a power struggle rather than some romantic blending, so blaming the British for creating a discord is totally wrong. At best they accentuated something which was latent. It is true that Muslim rulers co-opted Hindus into some form of power sharing, but so did the British. The point is that the Muslims dealt with Hindus from a position of strength. The Muslims lost this privilege when the rule passed on to the British. As and when the Indians studied abroad and learned about democracy and democratic institutions and started yearning for them as future goals, there was realisation among the Muslims that they would lose out in such a process because of their numerical strength vis-a-vis Hindus. In short, this struggle for power and having a pole position led to partition.

If one analyses the post-independence times, the power struggle between Hindus and Muslims continues. In states with large Muslim population, the community successfully negotiates its interests with political parties in lieu of its votes. In a state like Punjab where ethnic cleansing happened at the time of partition leaving no sizeable Muslims, there is no politics of Hindu-Muslim polarisation as exists in states like UP and Bihar with a significant Muslim population. However, in Punjab there have been instances of intra-Sikh group squabbles and even Hindu-Sikh rivalry for political ends. The point is simple: politics of polarisation can happen on issues of religion, region, caste and community. While Thapar in her analysis is fine with region and caste conflicts, she raises a red flag when it comes to religion.

Further, by blaming the British for categorising Hindus and Muslims into fixed religious groups by breaking past traditions, she’s forgetting that as societies move to modern times, such categorisation and documentation is required. The biggest limitation of the book is that it hardly covers the modern events in terms of analysing dissent. In post-independence period whether our Constitution has limitations or not in accommodating dissent, whether the various amendments to the Constitution starting from the first one, to various people’s movements, including the one led by Anna Hazare and Arvind Kejriwal, find no mention, but Shaheen Bagh does.

Thapar could have built a case for our growing intolerance, caste politics, politics of religion and region and growing parochialism, and how all these are ominous for a developing country like ours. However, such an exercise would have required deeper research in areas where she does not have expertise. It would not be wrong to say that Thapar is lazy in just remaining content with her period of specialisation and using it to make some general comments on modern times. Even die-hard Thapar fans and ardent Modi-haters would find the book dull and boring because of this limitation of hers.

Voices of Dissent: An Essay

Romila Thapar

Seagull Books

Pp 168, Rs 499

Get live Stock Prices from BSE, NSE, US Market and latest NAV, portfolio of Mutual Funds, calculate your tax by Income Tax Calculator, know market’s Top Gainers, Top Losers & Best Equity Funds. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

![]() Financial Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel and stay updated with the latest Biz news and updates.

Financial Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel and stay updated with the latest Biz news and updates.