By Katrina Nicholas, Keith Naughton, Gabrielle Coppola and Debby Wu

When the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami-ravaged Japan in 2011, ocean water flooded factories owned by Renesas Electronics Corp. Production at the swamped facilities ground to a halt—a major hit for Renesas, of course, but also a devastating blow to the Japanese car industry, which depended on Renesas for semiconductors.

Lacking chips for everything from transmissions to touchscreens, Honda, Nissan, and Toyota were forced to shut down or slow output for months. As the perils of just-in-time manufacturing and the dangers of relying on a single supplier for key components became obvious, automakers vowed to steer clear of similar snafus in the future.

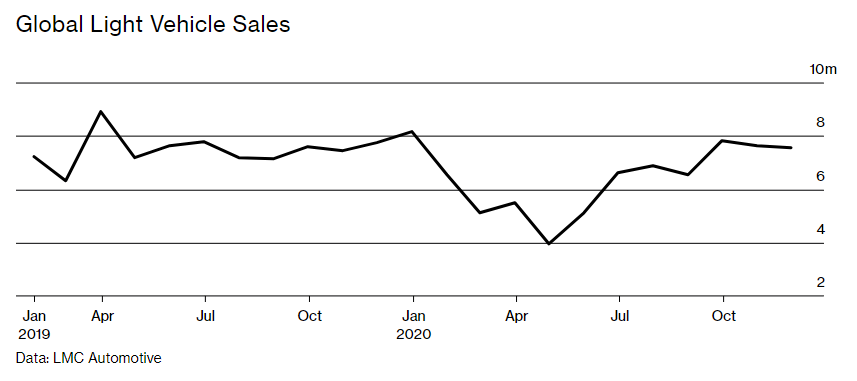

Yet a decade later, the global auto industry finds itself in an almost identical predicament. The catalyst for the breakdown this time is a slower-moving natural disaster: the coronavirus pandemic, which has disrupted the supply chain for makers of the electronics that are the brains of modern cars. That left automakers—which have long eschewed maintaining costly inventories of parts—scrambling to secure those components when sales rebounded.

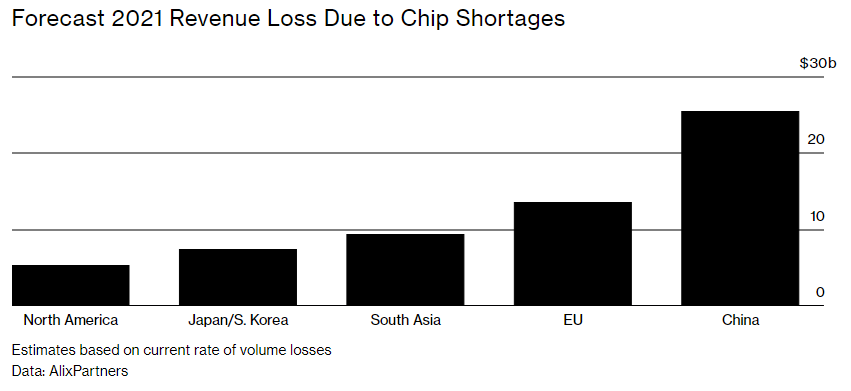

The shortage could lead to more than $14 billion in lost revenue in the first quarter and some $61 billion for the year, advisory firm AlixPartners predicts.

The industry is “wedded to ‘lean manufacturing,’ ” says Tor Hough, founder of Elm Analytics, an industry consultant near Detroit. “They have gotten in this mode of just managing for next week or next month.”

Cars these days are in many respects computers on wheels, with electronics accounting for about 40% of a vehicle’s value. By the time auto parts suppliers realized they were running short on the dozens of microprocessors needed for each car, chipmakers were slammed making semiconductors for the cellphones, game consoles, and computers that housebound shoppers were buying like crazy.

The problems have been exacerbated by the outsize power of a single company: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which accounted for 56% of global chip manufacturing revenue in the fourth quarter of 2020, according to researcher TrendForce.

Automakers rarely buy directly from TSMC, instead purchasing most of their electronics from suppliers that often outsource the design and manufacturing of chips to automotive-focused shops such as NXP Semiconductors NV and Infineon Technologies AG. Those companies make some parts in-house, but they hire TSMC to handle much of their production.

While the auto industry’s needs are enormous, they’re dwarfed by those of consumer-electronics giants such as Apple, Samsung, and Sony, which are “ready to pay more for chips to ensure their gadgets get to market on time,” says Jeff Pu, an analyst at GF Securities Co. “Carmakers are less inclined to do so.”

The problems started to bubble up a few days before Christmas, when Volkswagen AG said it was bracing for production disruptions because of a semiconductor shortage. Component makers Robert Bosch and Continental AG came next, saying they risked delays, then Nissan Motor Co. confirmed that a dearth of chips would force it to scale back manufacturing of its Note hatchback. After that, the announcements rolled in fast.

Fiat Chrysler idled plants in Canada and Mexico; Daimler said it was affected by the bottleneck; Honda slashed output by about 4,000 cars at a facility in Japan; Ford shut one SUV factory in Kentucky for a week and another in Germany for a month. Researcher IHS Markit says 628,000 cars—3% of global production—will be knocked off in the first quarter alone.

Yet for all the pain, automakers are reluctant to change their lean manufacturing strategies, because the savings they offer outweigh even the costs of disruptions like those they face this year. Carmaking is an inherently low-margin business, and producers are loath to build up expensive inventory because to turn a profit, the flow of parts into a factory needs to match the stream of vehicles coming out the other side. So it makes little sense to plan the entire operation around a worst-case scenario that comes only once a decade, says Kevin Tynan, an analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence. “It’s like driving a giant 4×4 SUV year-round waiting for maybe three or four snowstorms,” he says.

While the two sides publicly say they’re working together to fix the problem, in private each points a finger at the other. The chipmakers insist the car industry’s obsession with low inventories is to blame. Auto and parts producers counter that semiconductor manufacturers have favored consumer-electronics companies because those gadgets provide the bulk of their profits—an allegation chipmakers deny.

Regardless of who’s at fault, few expect the bottleneck to clear before the summer, and some say it will last into the fall. It’s not easy for chipmakers to add capacity, because most factories are currently running full-steam and new plants typically cost billions of dollars and take years to build. “It’s really going to have an impact through the first half,” says Matt Blunt, president of the American Automotive Policy Council, a lobbying group for Detroit automakers. “And the longer it takes to resolve, the more it will bleed into the third quarter.”