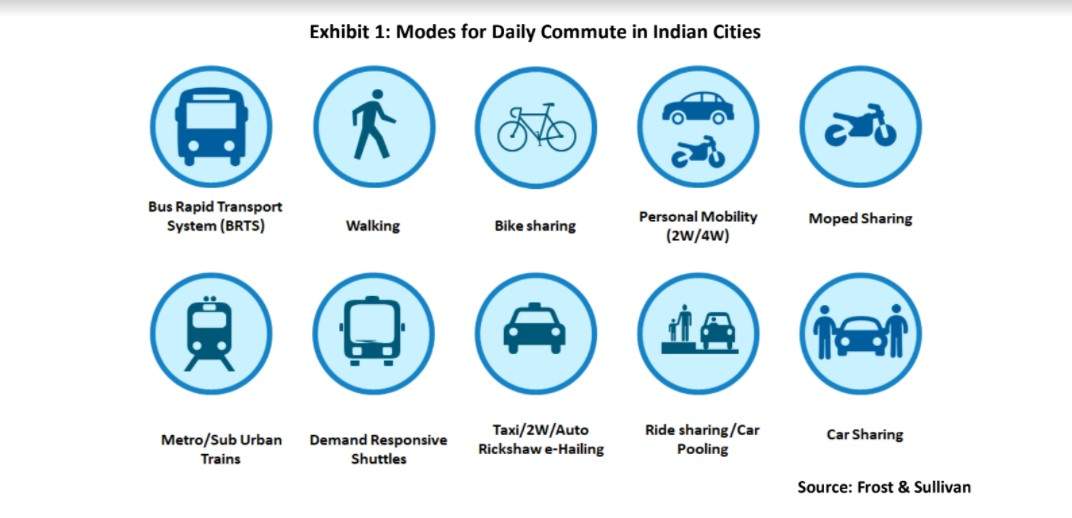

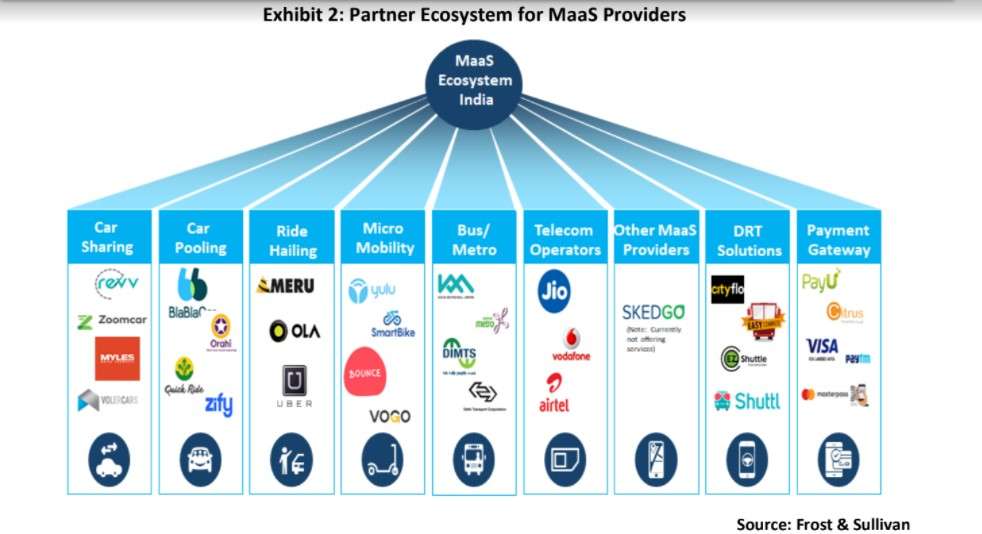

Car sharing falls under the larger umbrella of shared mobility, which includes other transport modes like taxis, two-wheelers, auto rickshaw ride hailing, and carpooling. Frost & Sullivan defines car sharing as a rental model for a short time, usually on an hourly basis, arranged through a mobile app or a website.

The car sharing business model in India differs from that in other regions, like Europe. For instance, one-way car sharing services—where cars can be rented for shorter durations like 20-45 minutes—are unavailable in India. Instead, the concept of one-way car sharing in India refers to a business model where cars can be rented in one city/location and dropped off in another city/location. The rental duration of such a service is typically at least six hours.

Pre-COVID, India’s shared mobility market was thriving. More than 20 players offered a range of shared mobility services across 160-plus cities.

A 2019 Frost & Sullivan customer survey of over 1,200 respondents from six major cities revealed ride hailing to be the most preferred/used option, led by heavyweights like Ola and Uber. The survey also highlighted the rising popularity of self-driving/car sharing business models like Zoomcar, which had a 10,000-strong fleet spread across 46 cities in the country. At its peak before COVID, India’s car sharing market had over 4 million registered users and more than 12,000 vehicles. Post-COVID, India’s shared mobility ecosystem will offer the perfect platform for launching mobility as a service (MaaS) solutions in which car sharing will play a vital role.

Rise of the car sharing model

Similar to most other mobility markets, the pandemic hit the car sharing market hard. However, this is viewed as a minor setback for a market that seems intent on speeding ahead. Sustained recovery will be supported by a clutch of demographic, regulatory, economic, and technological factors.

Millennials have been and will continue to be the driving force behind the uptake of car sharing in the country. For instance, Zoomcar’s growth is attributed to self-driving cars being the preferred choice of millennials for weekend getaway trips. Technology—whether in terms of distributed blockchain applications, expanding smartphone/internet penetration, or overall digitization facilitated by cloud services—has further underlined the credentials of car sharing as an efficient, reliable, and economical alternative to traditional car ownership.

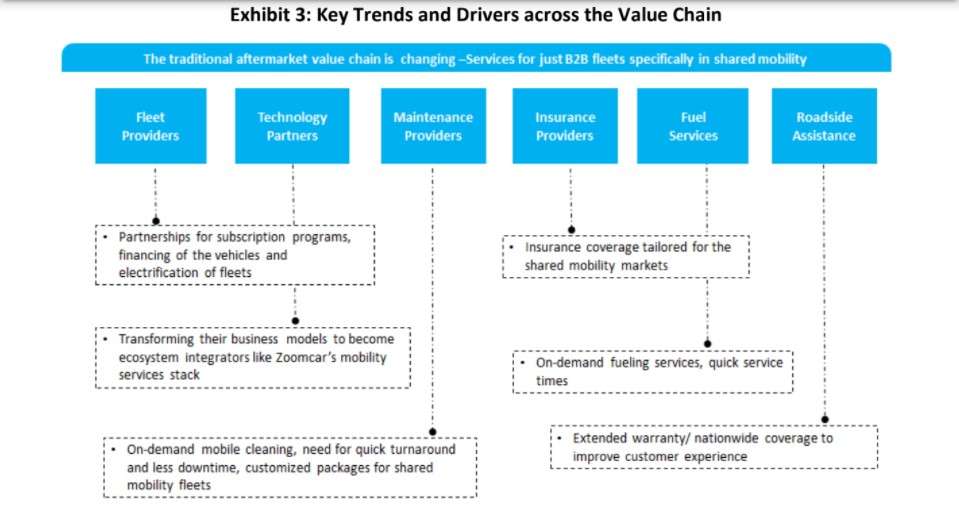

Meanwhile, government initiatives aimed at controlling urban congestion and emissions have incentivised the growth of electrified car sharing fleets. Sensing an opportunity, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) have sought to enter into strategic partnerships with car sharing service providers and provide the bulk of cars for their fleets or have decided to take the plunge themselves.

Subscription programmes are another interesting trend that began pre-pandemic. Such programmes have garnered further interest from the market as the pandemic wanes.~

For instance, Hyundai invested in and launched a vehicle subscription programme with Revv. Similarly, Mahindra collaborated with Zoomcar on electrification initiatives and supplied vehicles to its fleet, even as it launched its EV shared mobility service, Glyd, in 2019. Tata Motors’ partnership with Myles and Zoomcar and Ford’s investments in Zoomcar have highlighted continued OEM confidence in the growth prospects of the car sharing business. In 2019, MG Motor India announced a tie-up with Myles to create “disruptive car ownership solutions.”

Changing mobility preferences

One of the key trends that we expect to emerge over the next few years is accelerated fleet electrification. Car sharing is increasingly shifting toward green vehicles, primarily because of the push from cities. Many cities are under pressure to meet their zero-emission goals and are trying to promote shared mobility modes and reduce private car usage. Zoomcar plans to increase the number of electric cars in its fleet from current levels of 2%-5% to 30%-35% within the next couple of years.

Subscription programmes are another interesting trend that began pre-pandemic. Such programmes have garnered further interest from the market as the pandemic wanes. Several OEMs are partnering with car sharing operators to offer flexible ownership options to customers. Hyundai, with a first-mover advantage, is now in 20 cities. It has a deal with Revv and Mahindra to offer subscription services. Other car subscription companies in India are Zoomcar, Zap Subscribe, and MyChoice.

Car sharing operators in Europe have remodeled their pricing and packaging strategies to strengthen their relevance during the pandemic. Measures adopted by operators include long-term rentals (3-10 days), bundled pricing, ride passes for specific use cases like corporates, advanced booking options, and vacation rentals. The overarching strategy here has been to cover all use cases of car sharing. This is something that can be explored in India as well once the pandemic eases.

The utilization of car sharing fleets represents a major challenge for car sharing operators. Diversifying their solutions for specific use cases like car sharing for hotels, residential complexes, and airports can improve utilization rates. Car sharing operators are beginning to partner directly with real estate developers to offer exclusive car sharing programmes in developed properties.

In a post-COVID landscape, the traditional aftermarket value chain will further transform, moving beyond offering services for just B2B fleets to targeting shared mobility fleets as well. Aftermarket services like maintenance and cleaning for shared mobility fleets will necessarily shift to on-demand business models that support faster turnaround times and reduced downtime. We have seen similar partnerships in other segments; for example, Uber’s partnership with Shell provides benefits across fuel, lubricants, coolants, and car care products to enhance average net savings for drivers by 10%-20%.

The road ahead

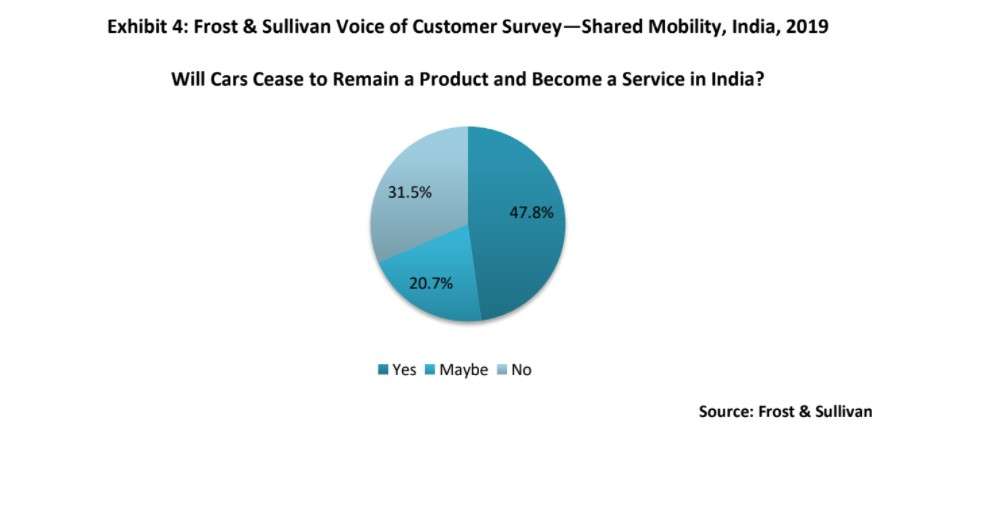

So how does all this play into the car ownership versus car sharing debate in India? In Frost & Sullivan’s pre-COVID customer survey on shared mobility, almost 48% of respondents said they agreed with the idea that “cars would cease to remain a product and become a service,” while about 32% disagreed. The implications here are that car sharing is a “service” as opposed to car ownership, which focuses on the car as a “product.”

Car ownership will continue to face challenges related to poor road infrastructure, traffic congestion, stricter emission controls, and scarce parking. However, pent-up demand and health and hygiene concerns post-COVID will, undoubtedly, spur car ownership. Such trends are likely to receive a further fillip once government-backed smart city plans come to fruition.

It is also worth noting that nearly 30% of respondents in the Frost & Sullivan customer survey stated that they had used car sharing/self-driving services. Working people, the self-employed, and students were among the most frequent users of such services. Trends indicate that the customer base for such services will expand in tandem with enhanced use cases, greater flexibility, improved cost, and convenience benefits.

A win-win for customers

COVID-19 has changed market dynamics, and what used to be considered “normal” before last year may well become obsolete in the coming weeks. This means that every industry will need to adapt to the new normal, even as customer preferences also change post-pandemic.

We expect the Indian car sharing fleet to increase from about 12,000 to 40,000 vehicles during 2020-2025 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 27%. The car sharing market in India is currently quite consolidated, with the top two operators holding a majority of the market share. As seen in other business models, we are likely to see local operators expand their presence to international markets. Zoomcar, which dominated the Indian car sharing market, plans to list in the US markets via the Special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) route. Zoomcar plans to expand to markets where car ownership rates are low, but population movement is higher.

We are betting big on car sharing; emerging trends and opportunities are setting the stage for car sharing companies to regain the momentum they lost in the past 16-17 months. In essence, in the battle for the minds and hearts (and wallets) of India’s mobility consumers, the ultimate winner will be the customer—and just as well.

(Disclaimer: The author is program manager of mobility practice at Frost & Sullivan. Views expressed are personal)