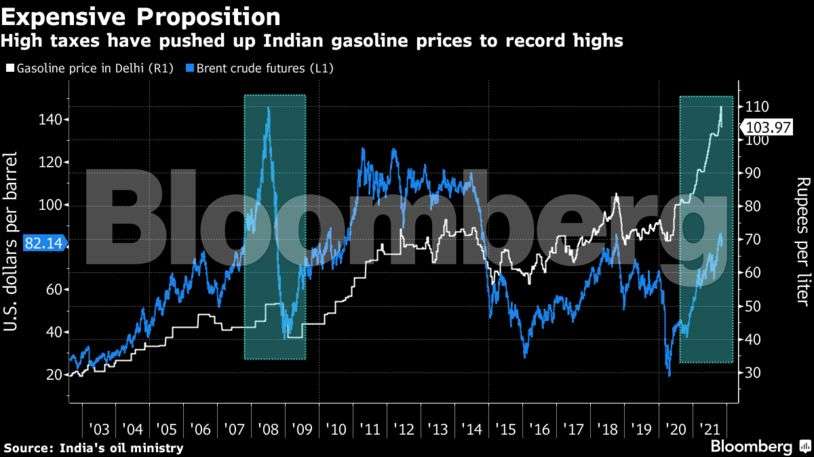

The highest fuel prices in India’s history are spurring efforts to shift the nation’s ubiquitous motor scooters — which account for nearly 70% of local gasoline consumption — to electric models, along with a new pledge to hit net-zero by 2070.

At current prices, even the most fuel-efficient two-wheeler guzzles gasoline worth more than Rs 100 for a 100-kilometer ride, while an e-scooter can run the same distance at less than a sixth of that cost.

Companies like Hero Electric Vehicles Pvt. and Ola Electric Mobility Pvt., a unit of India’s biggest ride-hailing services provider Ola, are launching new two-wheelers priced around $1,000, roughly what the country’s top-selling gasoline motorcycles and scooters cost.

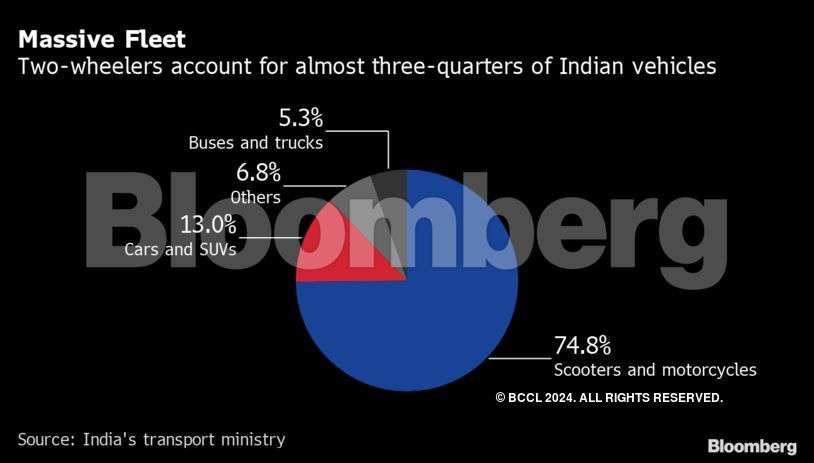

With two-wheelers accounting for 80% of vehicle sales in a country where public transportation is inadequate and cars are out of reach for most, the potential for growth in the electric segment is enormous: BloombergNEF expects electric motorcycles and scooters to account for 74% of all such vehicles sold by 2040, up from less than 1% now.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s surprise announcement at the COP26 climate summit that the world’s third-biggest carbon emitter will reach net-zero by 2070 is also expected to inject new life into the transition effort.

“There is no denying the fact that the move to electric is inevitable for two-wheelers,” said Varun Dubey, chief marketing officer of Ola Electric. “I don’t think there is any convincing required to the consumer to switch to electric.”

Still, sizable hurdles remain, like the lack of a nationwide charging infrastructure. Subsidies for consumers to switch to electric — 15,000 rupees ($202) per kilowatt-hour — are measly by global standards and there aren’t special perks like in China, where electric scooters can use bicycle lanes.

India’s emissions goal will required trillions of dollars of investment and Modi’s government has not made clear how it intends to raise the funds, besides saying that rich nations must do more.

It’s in India’s interest to stem global warming, even if the problem was caused mainly by carbon dioxide accumulated in the atmosphere by countries that industrialized first. The nation of 1.3 billion people is one of the most vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather events like heat waves and floods. Disruptions to the rainy monsoon season are already having a major impact on agriculture.

The country’s vast fleet of two-wheelers is seen as relatively low-hanging fruit in its efforts to lower emissions: consumption of gasoline to power personal transportation has more than doubled in the decade through March 2020. Motor fuel is the second-most consumed oil product in the country, accounting for almost 15% of oil demand.

The economic disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has brought growth concerns to the top of Indian monetary policy makers’ priority list, and relegated the inflation goal to a secondary position, minutes of the six-member Monetary Policy Committee earlier this month show.

New entrants are piling into the space, including Ampere Electric and Ather Energy. The country’s top two gasoline two-wheeler makers are also pivoting: Bajaj Auto Ltd. launched an electric scooter last year, while Hero MotoCorp Ltd. will unveil its first by March.

The sector is led by Hero Electric, which sold 54,000 units in the year ended March, more than a third of all electric two-wheelers bought in that time period. Still, it’s a fraction of more than 15 million gas-powered ones sold.

The newer electric models go some way towards addressing concerns around travel range and charging. Ola is shipping its scooter with a charger that can be plugged in at home, while Hero has a modular battery that is removable for charging.

Some of these vehicles have a range of as much as 210 kilometers on a single charge, enough for a week’s commute in some of the country’s largest cities, and the companies are also building more charging points across the country.

But the availability of charging facilities across India remains inadequate compared to China or western economies, which make long journeys out-of-reach. Oil Minister Hardeep Singh Puri said this week that India’s oil companies would set up charging stations in main cities and on national highways.

Another hurdle is the massive size of the Indian two-wheeler fleet, which will “take a lot of time to turn over through the fleet and replace existing vehicles,” said Cuneyt Kazokoglu, head of oil demand at London-based energy consultancy FGE.

There is also little consensus around the sector’s growth forecast: the country’s biggest oil refiner Indian Oil Corp., projects that the share of electric two-wheelers is likely to be only 30% of sales in 2030. FGE sees just 5% of total scooter sales around 2025 to 2030 being electric.

Nevertheless, Indian refiners have already started shifting away from gasoline and diesel, efforts which will likely be accelerated after Modi’s pledge.

Indian Oil has started battery swapping for electric vehicles at some of its refueling stations while Reliance Industries Ltd., India’s most valuable company and operator of the world’s biggest oil refining complex, plans to make its operations carbon neutral by 2035.

What industry players want now is a stated goal from the Modi government on phasing out gas-powered two-wheelers.

“In the absence of concrete conversion targets, it’s difficult for companies to make concrete plans,” said Naveen Munjal, an industry veteran who launched India’s first electric bicycle in 2001 and its first e-scooter in 2007. He’s now the managing director of Hero Electric.

“If there is a policy in place that we have to convert by 2025 or 2030, then the whole ecosystem will fall in place,” he said.