The very first time I saw him was at a buffet after a press conference in one of the 7-star hotels in Central Delhi. Dressed in a casual T-shirt and jeans, not a hair on his head, Chanchal Pal Chauhan was busy tackling a piece of mutton. I am not much of a foodie myself but I found that amusing. When I recall that moment now, I recognise there was a childlike innocence in it.

The next time, Chanchal–CPC to some, Chanchal San to most, and simply Maalik to me, was going full tilt in a small car that wasn’t meant for racing. That was a common note–all automotive journalists go a tad mental behind a steering wheel. I knew then, there was no other way we wouldn’t be friends. Chances were very high we would become the best of friends but that is more down to his strength of character and generosity than anything else.

All of 46, Covid snatched Chanchal from us in April, at the peak of the second wave. It left us numb and shattered a part of me–forever. Six months have gone by and yet it feels too raw. The mind has not been able to process his departure. Maybe it won’t ever. A stop-start year that this has been, automotive events–press conferences, interviews, meetings and launches–have not been as frequent. In a way that has been a blessing because every time an event has happened, Chanchal’s name always came up. Fellow journalists would reach out to your’s truly and Pankaj Doval from Times of India to tell us how badly he is missed. Or how much poorer the industry is now. Nobody knows this as much as we at ETAuto where Malik gave the last two of a glittering 20-year career.

As a professional, he played hard but fair. There is not one company that he would not have given grief to in his career. Yet everybody counts him as a friend. I use the present tense here deliberately. As journalists we meet some people many times and many people a few times. Chanchal always left an impression even on those whom he met only a few times. It is a rare quality.

The ability to mill around with people of all kinds gave him an edge over the others. Case in point was the story he broke on how union leaders of Maruti Suzuki’s factory in Manesar quietly retreated to the shadows after accepting generous pay outs. It was a result of his strong connect with the workers. By that time, we had all spent days outside the factory building sources within the workforce but Chanchal had managed to forge the strongest of bonds.

With experience, he developed the ability to foresee what is in store in the future–another important quality in a journalist. At ETAuto, one of his most successful stories was when he predicted that Harley Davidson would soon wind up in India. He had back then also hinted that Ford would follow the same route. It came true too, barely five months after his death.

The last time I saw Chanchal, it was in Goa in February 2021. We were together for one more of the many media test drives we have shared over the years. Anybody who knew him personally, would know he was a man who lived life to the fullest–cliche as it may sound. He had an enviable appetite for all good things in life and loved a good party. That evening he was on fire. Almost as if he knew somehow that the party was soon coming to an end.

Maruti Man

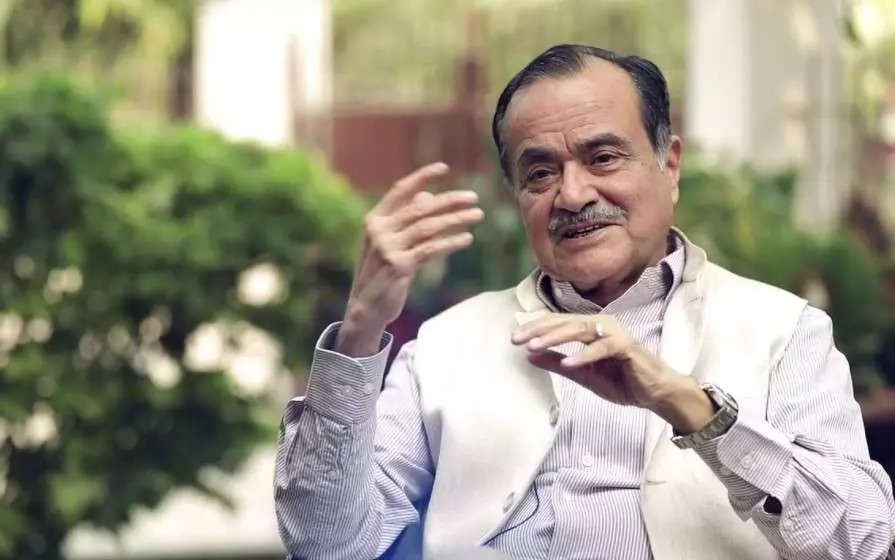

This year the industry also lost one of the finest executives we have ever seen or shall ever see–Jagdish Khattar. Barely 72 hours after Chanchal in April, Khattar san succumbed to a cardiac arrest. Shock is not a word one would generally use for the demise of a septuagenarian but it is still apt in his case. In his 78 year old body, he still had the brain as sharp as that of a 40 year old.

An arts graduate from the prestigious St Stephen’s College in Delhi, Khattar san went on to acquire a degree in law and joined the IAS. In the government he excelled at whatever he did rising through the ranks to become a joint secretary in the ministry of steel but his crowning glory was in the private sector. Under his stewardship, India’s largest carmaker Maruti Suzuki made the smooth transition from a PSU to a private firm as the government bowed out in 2007.

With its first mover advantage that dates back to the early 1980s, Maruti always had an advantage over the others. But to retain its vice-like hold in a market that has attracted the best in the business across the world wasnt an easy task. It did not help that soon after he took over the corner office at what was then called Maruti Udyog Ltd, the company faced a debilitating 90 day workers’ strike at the Gurgaon factory. They were demanding higher wages.

At a time when multinational companies were entering India in droves, this would have raised costs and made the company even more inefficient. With the support from Suzuki, which was then a minority shareholder, Khattar dug his heels in and dealt with the workers with an iron hand. It was a pivotal time for the company where the relationship of its two main shareholders –Suzuki in Japan and government of India, had soured. Khattar san not only rebuilt the company so that it can hold its own against the challengers, he also helped bridge the trust deficit between the government and Suzuki.

“The 2001 strike was one of the toughest periods that I came across in Maruti Suzuki. It was actually the turning point,” he reminisced in 2007 when he was leaving the firm. “If we had given in, we would not be where we are today. Salaries would have gone up and we would have become inefficient. Our competitiveness in the market would have been blunted.”

The strike impacted the company’s position in the market as its share fell from a commanding 79 per cent in January 1999 to just 51 per cent a year later and a new low of 42 per cent in June 2000. Khattar nursed the company back to health before hitting back at the competition with a flurry of launches that included Wagon R, Alto 800, the original Baleno sedan and Altura station wagon as also a revamped M800, which was at that time the best selling car in the country. By June 2001, Maruti had clawed back to 60 per cent share.

In the process Khattar san earned himself the moniker of being the Lee Iacocca of motown in India. The fortress that Maruti is today has a lot to do with Khattar san’s business acumen. After his retirement from Maruti in 2008, he gave in to his entrepreneurial zeal to launch Carnation–an innovative multi brand service network for cars. The idea was simple–he knew the inefficiencies of the traditional automotive retail network and wanted to disrupt it with more affordable and quality service for customers.

Unfortunately, it did not take off and Khattar san spent the last few years of his life fending off lenders. But he had not given in and that razor sharp brain was still churning out new ideas. Those eyes were still full of dreams. Some of them would surely have taken off in the new venture capital funded economy. If only that heart had cooperated a bit more.

Wherever they are, Maalik and Khattar san must still be having a tug of war up there. Chanchal nibbling away with his questions, waiting for Khattar-san to let his guard down.

Also Read: