The crisis facing billionaire Gautam Adani has revealed a potential pitfall in India’s ambitious plan to reduce emissions: its reliance on the country’s most affluent and powerful private citizens.

Led by Adani’s $70 billion pledged investment in green energy infrastructure, India’s tycoons have so far committed to spend far more than the government on the energy transition. Reliance Industries Ltd.’s Mukesh Ambani and JSW Group’s Sajjan Jindal, along with energy giants like Tata Group, have also rushed to champion the shift to a cleaner future.

But Hindenburg Research’s allegations about companies linked to Adani Group have raised doubt on the firm’s future, including its massive green energy investment. It’s also created problems for Adani Green, the group’s renewable energy arm. The storm engulfing Asia’s now second-richest man also threatens to spread to the other conglomerates; Hindenburg Research has raised questions about the country’s corporate governance.

Because Adani group is a dominant player in India’s clean energy industries, the pace of investment might slow, said Ashiwni Swain, fellow at New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research. “We cannot bank on two or three companies to reach our goals. We need a populated sector,” he said. “There are other players and many more will join to take the journey forward.”

India’s national climate blueprint sets 2070 as a goal for net zero emissions, 10 years after China and two decades behind Europe. India will continue to expand its coal power fleet to alleviate energy shortages, prompting the government last month to defend its use of fossil fuels while in the same breath vowing to to remain committed to decarbonization.

To meet its goal, India requires investment of $160 billion annually through 2030, roughly triple today’s levels, according to the International Energy Agency. Foreign direct investment, while growing, remains a fraction of current commitments. Adani’s rapid downfall may undermine investor confidence in India more broadly, threatening to curb capital flows into the nation for green financing.

The gap highlights the government’s dependence on its private sector to hit its green goals. While private capital will be needed to fight climate change all over the world, the sheer size of India’s challenges makes it more reliant on its richest citizens and most sprawling companies.

Executives have so far been happy to oblige, as the prize is a top-spot in the lucrative industries of tomorrow. Adani and Reliance’s Ambani are vying to become the single biggest investor in India’s green sector, with the billionaires constantly one-upping each other with fresh announcement of giant manufacturing plants and some of the world’s largest projects.

Adani has often aligned his businesses with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s development goals and is characterizing Hindenburg Research’s charges of fraud as an attack against his home country. At the same time, Power Minister Raj Kumar Singh told reporters in New Delhi on Thursday that there are more than a dozen large firms that can push India’s agenda forward.

Adani, who made his billions on the back of his coal empire, positioned himself as one of the leading advocate for new and experimental green technology. He is planning enormous solar and wind manufacturing centers across the country, and developing a supply chain for the world’s cheapest green hydrogen aimed at positioning India as an exporter of the clean fuel.

But some environmental advocates point out that Adani and his company were never that green to begin with. Adani doubled down on coal production last year as Modi promised to bring reliable electricity to more Indians amid a global fuel supply crunch. The group’s mining operations account for at least 3% of global CO2 emissions from coal, according to SumOfUs, an activist group that runs campaigns intended to apply pressure to powerful corporations.

“India is lot more than Adani. Their role in India’s energy transition is disputable,” said Assaad Razzouk, chief executive officer of Singapore-based renewable firm Gurin Energy. “It is very dangerous to confuse the energy transition in India with one group’s perspective or market power.”

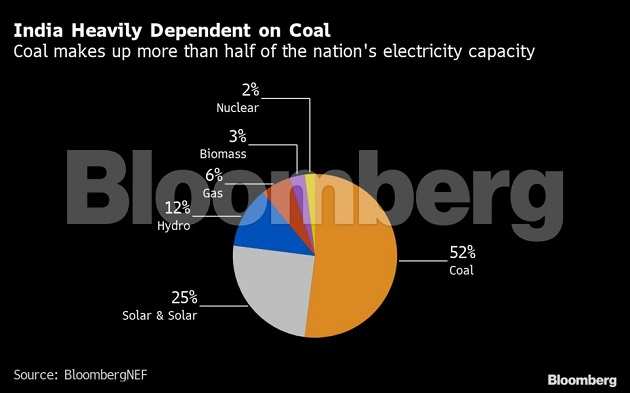

India plans to decrease the share of fossil fuels in the nation’s electricity mix to 50% by 2030, down from more than 57% today. India still relies heavily on coal for power generation, with demand for the dirtiest fossil fuel expected to inch higher through 2025, and critics say the government needs to do more to limit global warming.

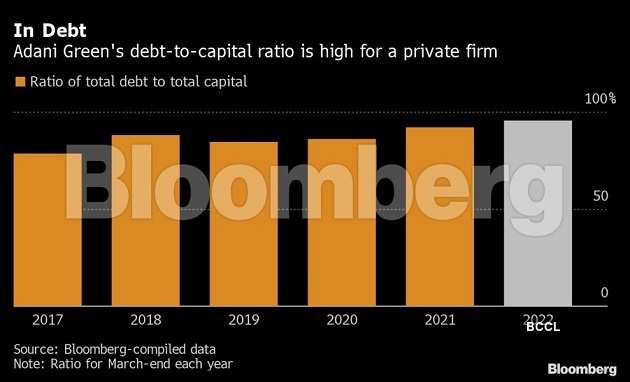

The most immediate near-term consequence of the current Adani rout is that it will be more difficult for the billionaire to raise money to fuel its green expansion. There’s also an open question about the debt at Adani Green Energy Ltd., the unit that is developing renewable projects. The debt-to-capital ratio for the firm soared to 95.3% in the previous fiscal year ended March, according to Bloomberg calculations. It has since declined to 88.5% but remains higher than its peers.

Adani Green has the highest funding risk of the group companies due to its weak balance sheet, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analysts, adding that the firm has $1.25 billion worth of bonds due next year. “Adani Green Energy’s cash as of September cannot cover short-term debt maturities,” the analysts said.

“Will this damage Adani? Categorically. It should have already,” said Tim Buckley, the director of the Sydney-based Climate Energy Finance think tank and a long-time observer of the billionaire. “You’ll find a lot of Western capital will now avoid the Adani group. It is going to put Adani’s ability to access global western capital, and in particular green capital and ESG capital,” at risk.