By Rajeev Singh, Sumit Mishra and Saket Mehta

India is expected to become the third largest by 2026. In spite of a scrapping policy, the scrapping of vehicles is not yet commensurate with the growth in production of the new ones. It is mainly because of the unorganised and small-scale nature of the scrapping sector. This has led to an increase in the number of obsolete vehicles, also called end-of-life vehicles (ELVs), which either rot on roads, or are disposed of in an unscientific manner, risking public health and environment. According to a Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) study, the number of obsolete vehicles is expected to grow from 8.7 million in 2015 to 22 million by 2025 creating more challenges for the country.

The ‘voluntary vehicle – fleet modernisation programme or the ‘vehicle scrappage policy’ is expected to help reduce pollution, generate demand for new vehicles, and create a new business area of scrapping and reclaimed metals and other materials.

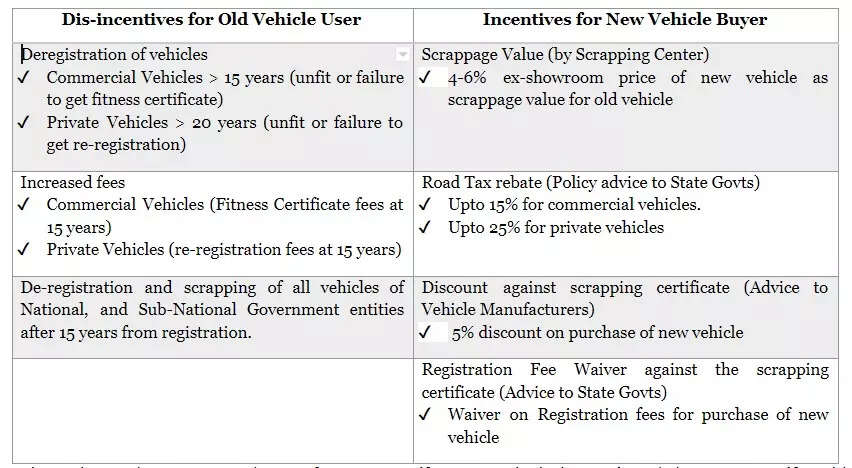

The policy is having a good mix of incentives (for new vehicle buyers) and disincentives (for old vehicle owners), and so it is likely to promote vehicle scrappage and create demand for new vehicles.

The various incentives and disincentives proposed under the Vehicle Scrapping Policy, 2021 are presented below:

New vehicle demand

Global experience suggests that policy can act as a tool to stimulate auto demand. The policy being balanced is expected to create a positive effect on buyers to go ahead with scrapping of their old vehicles and buying of new ones, and once the benefits are realised, it is expected to create a multiplier effect leading to the desired impact on the sale of new vehicles in the country.

As per the CPCB estimates, the number of obsolete 4-wheelers in the country by 2025 will be:

· Passenger vehicles (LMV): 2.8 million

· Commercial vehicles (MCV & HCV): 1.28 million

The estimated number of obsolete vehicles is high and so is the potential. But the success of the policy will hinge on commercial benefits from scrappage vis-à-vis the current practices of resale, and its strict enforcement.

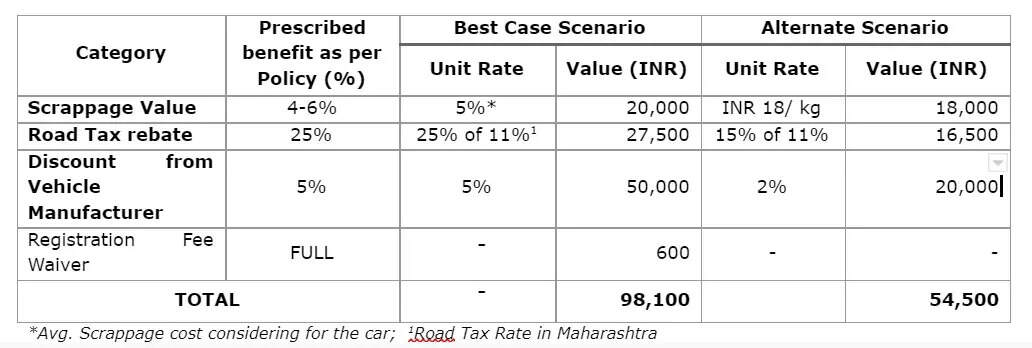

An example of the commercial benefits for a new passenger vehicle buyer who also avails scrappage benefits for old vehicles is worked out below.

New mid-market car (petrol): INR 10,00,000 (ex-showroom Mumbai)

Old car mass-market (petrol): INR 4,00,000 (ex-showroom Mumbai) | Weight Assumed: 1000 kg

Based on the example it can be seen that the actual benefit to the buyer can be in the range of INR 54,500 (assuming a certain scenario) to a maximum of INR 98,100 depending on the actual incentives extended by the state government and the vehicle manufacturer. The benefit range being large could be a make or break for execution of the vehicle scrappage policy. Though the policy benefits are good, a lot depends on the state government and OEMs.

Recycled steel

Recycled steel is used in the manufacturing of automobiles, and a regular passenger vehicle uses about 25% recycled steel out of its total requirement. Hence, there is good demand for recycled steel in automobile manufacturing. However, the availability of scrap for secondary steel manufacturing is a major challenge in India, and the country is dependent on import of scrap which leads to an increase in the cost of production.

A vehicle scrapping industry using best-in-class technologies for scrapping obsolete vehicles is likely to increase the availability of recycled raw materials manifold. For instance, approximately 65% of a vehicle comprises metals, with a large part of the remaining components being made of plastic, rubber, glass, etc. Hence, a lot of metal scrap can be made available for reuse if the process of scrapping is scientific, leading to reduced input costs for vehicle manufacturers.

The OEMs having their presence in steel manufacturing (especially secondary steel manufacturing) will be able to leverage this to the maximum. Other OEMs can tie-up with their steel suppliers and work out an arrangement to supply steel scrap and take the benefit. But the actual benefit that can be realised by an auto manufacturer will depend on the efficiency of the logistics network for aggregation and scrappage being developed.

New business area

The policy will help in formalising and scaling up a new business area of ‘Scrappage Yard’ or ‘Registered Vehicle Scrappage Facility’ (RVSF) which has been unorganised and primarily comprised small-scale players.

To deal with the obsolete vehicles systematically and scientifically, by 2025 the country might require about 65-100 RVSFs. If the backlog and future growth are taken into account, the need for such facilities will be more. Hence, the business potential is huge.

The OEMs can leverage their current dealership network to develop customer loyalty programmes (buy-back schemes) and offer better value for the new vehicle to such buyers who plan to scrap the same brand vehicle with them.

A Deloitte study has found that the traditional model of passenger vehicle ownership is expected to change to a subscription-based model in the coming years. In its survey 72% of the respondents were willing to opt for ‘subscription to a brand’ model where they can select multiple vehicles for subscription from the same brand.

Hence, new business models with forward and backward integration in the value chain are expected to emerge in the automotive sector creating opportunities for the OEMs to innovate.

(Disclaimer: Rajeev Singh is Partner and Automotive Leader, Deloitte India. Sumit Mishra, is Director, Deloitte India, and Saket Mehta, is Associate Director, Deloitte India. Views expressed are their own.)