By Syed Shazil Hussain

New Delhi:

India’s rapidly growing vehicle fleet, air quality challenges, ambitious greenhouse gas emissions targets and a substantial oil import bill makes it understandable why India has decided to increase the ratio of ethanol blended with petrol to 20% and also accelerate the roll-out by bringing forward the E20 goal from 2030 to 2025.The E20 goal of 2025 requires large increases in ethanol from sugar and grains. A new report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) shows that generating solar energy to recharge electric vehicle (EV) batteries would be a far more efficient use of land than growing crops for ethanol.

Comparative land use efficiency

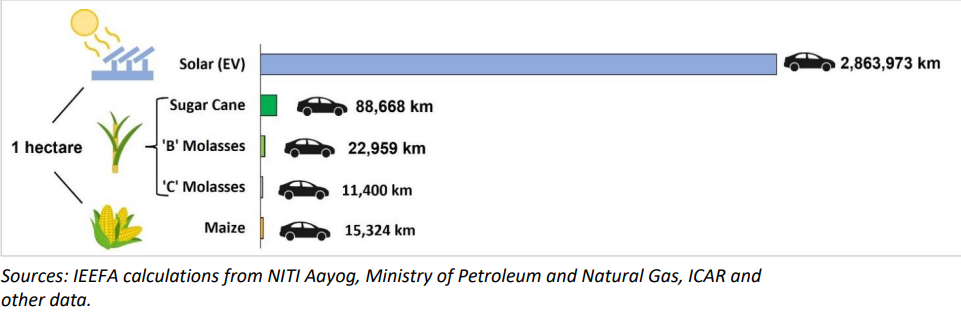

The report shows that the distance driven by EVs recharged from one hectare of solar generation would require ethanol derived from up to 251 hectares of sugar cane or 187 hectares of maize – even accounting for losses from electricity transmission, battery charging and grid storage.

In a U.S. analysis report, one analysis estimated solar for EV recharging as being over 70 times more efficient in land use than corn (maize)

For the solar to EV estimate, this same analysis reported a figure of 710,250 miles per acre of solar, which in metric terms is 2,824,505 km/ha – a difference of only 1% from the estimate obtained above for India and providing some confirmation of its validity.

A separate study also found a substantial 29-fold higher land use efficiency for solar than for corn-based ethanol in the U.S., with land use estimates broadly comparable to those reported here.

The ethanol-blending target or E20, will require a doubling of ethanol from sugar and quadrupling of ethanol from grains in just four years, with significant land use implications.

Sugar cane used solely for ethanol is the most land-efficient of the distillation options, but it produces no sugar, whereas making the ethanol from ‘B’ and ‘C’ molasses yield about 7.4 and 8.9 tonnes of sugar per hectare of cane respectively, partially offsetting the land use inefficiency.

Increasingly, ‘B’ molasses is used for ethanol, and other products such as juice and syrup are also playing a part.

Although this co-production of sugar has real economic value, any increased production for ethanol would need to account for its limited nutritional value and the environmental costs, especially if it displaced other crops.

Unlike sugar cane, maize growing has some potential for the same land to produce a second crop, predominantly as a rabi crop such as wheat, although yields are very dependent on soil moisture levels on rain-fed farmland and there is significant geographical variation in crop rotations.

Maize for ethanol also creates the by-product of Distiller’s Dried Grains with Solubles (DDGS), used largely in poultry fodder. Approximately 900kg of DDGS comes from each hectare of maize.

Although this may substitute for soya used in fodder it still represents much less efficient land use if considered in terms of direct food production for human consumption from the equivalent land, as per the report.

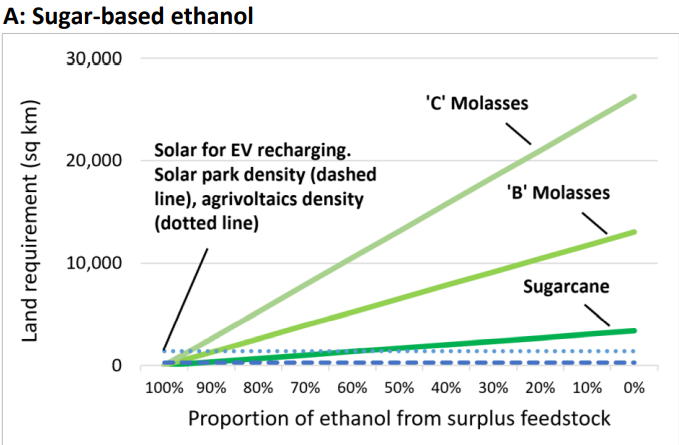

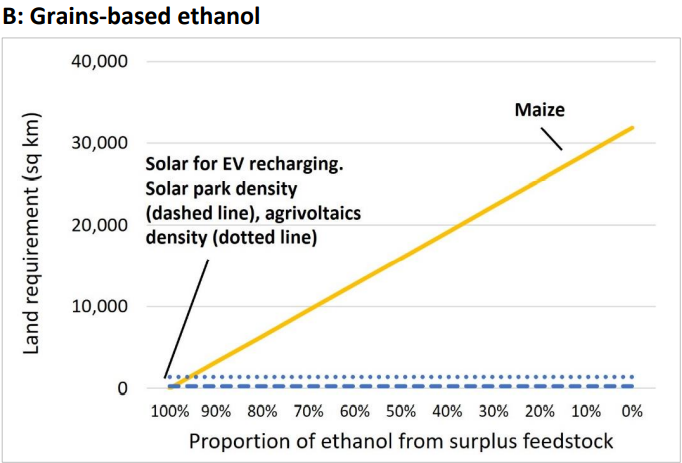

An additional consideration is that the renewable energy used to power the equivalent EVs need not be generated by high density solar parks. If it were to come from agrivoltaic projects at one-fifth or even one-tenth of the land density, it would still be many times more land-efficient than ethanol, while enabling agricultural production to be largely maintained.

These off-setting factors have effects in both directions but make little fundamental difference to the disparity in land-use efficiency of the various alternatives.

While surpluses may be sufficient for the component of new ethanol earmarked for sugar, up to 30,000 sq km of land may be needed for the additional ethanol planned for grains (maize).

“While the government’s promotion of ethanol blending in petrol may seem like a way to ease the burden of soaring crude oil prices, it further increases the pressure on agricultural land just as the war in Ukraine threatens the world’s grain supply. This intensifies the competition between energy and food and raises the stakes for wise land use in India significantly,” the report author Charles Worringham said.

“Although Russia has an 11% share of global oil exports, 26% of wheat exports come from Russia and Ukraine, and 16% of corn exports. In the end, food trumps energy for claims on arable land if the food supply comes under pressure.”

“A re-evaluation of the ethanol-blending policy and alternatives is needed urgently given that its targets have been brought forward to 2025 from 2030,” Worringham said.

Also Read: