Queenly, a marketplace for formalwear, launched into a world where its core product of dresses and gowns had a massive competitor, bigger and more elusive than Poshmark: quarantine.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused the fancy in-person events that one might attend, such as award shows, pageants, proms and weddings to be canceled to limit spread. But despite the fact that you might be rocking sweats over slacks, Queenly co-founders Trisha Bantigue and Kathy Zhou say that they had half a million in sales last year, and over 100,000 people visit their website everyday.

“So many women bought dresses to just dress up and feel normal at home, when everything else around the world was not,” Bantigue said. “It helped them feel grounded and stabilize themselves in this crazy chaotic pandemic environment.” The canceled events have also found new homes, such as Zoom weddings, Twitch pageants, socially distant proms and graduation car parades. The co-founder added that content creators on TikTok and YouTube have also bought Queenly dresses.

Pandemic growth added a surprising dimension to Queenly’s business, and the Bay Area startup is currently partaking in the Y Combinator winter cohort to navigate it. So far, it has raised $800,000 to date from investors including Mike Smith, former COO of Stitch Fix, Thuan Pham, former CTO of Uber, and Kelly Thompson, former COO of Samsclub.com and Walmart.com. The goal, the co-founders tell me, is to become the StockX for formalwear.

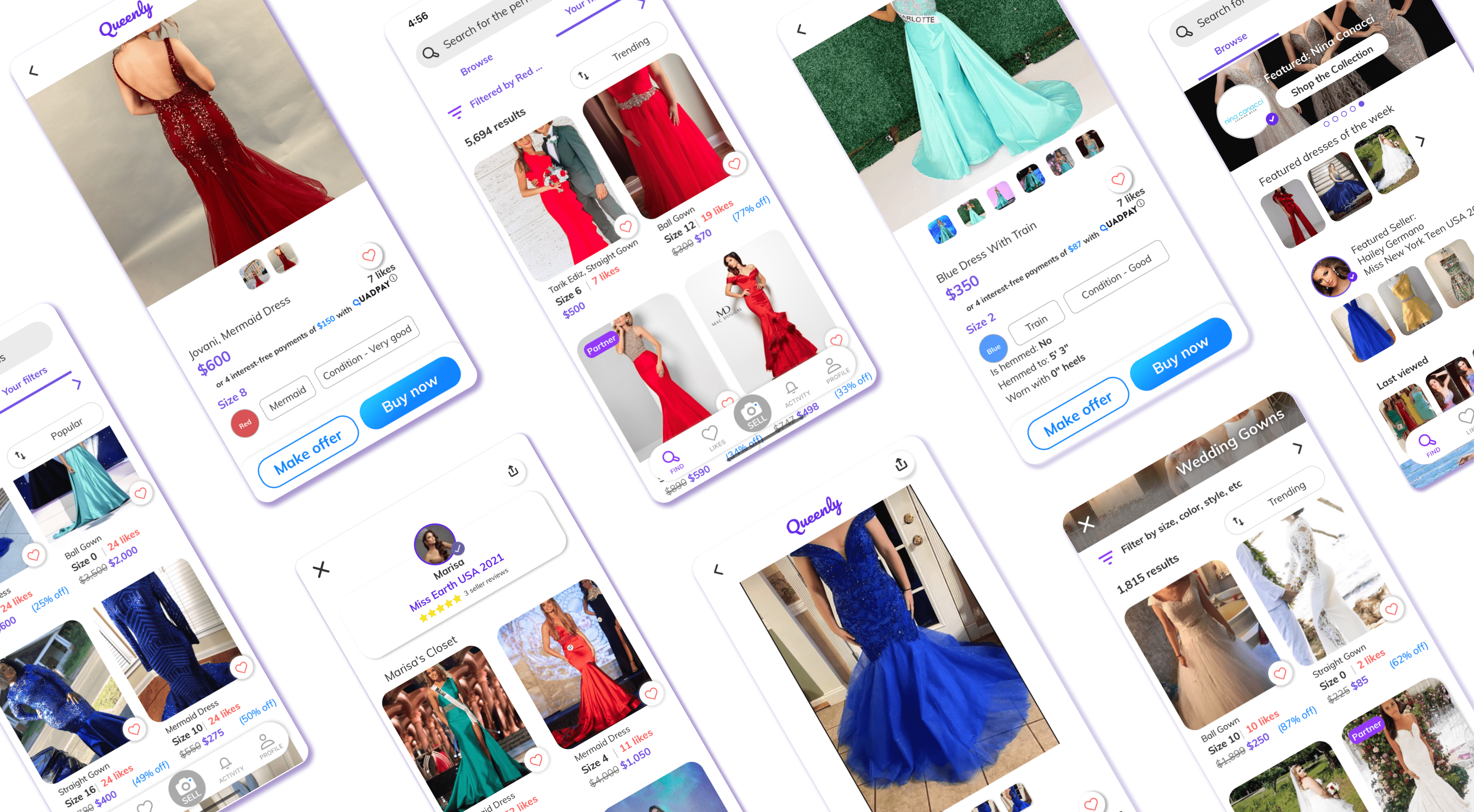

Queenly is a marketplace for buying and selling formal dresses, from wedding dresses to pageant gowns. The 50,000 dresses on the platform are either new or resale, and sellers get paid 80% of the price that the gowns go for.

Part of the company’s biggest sell, according to the co-founders, is its algorithm that matches buyers to dresses. Before Queenly, Zhou was a former software engineer at Pinterest who helped build content creation flows and the back end of the platform. She took the same focus that her and her Pinterest co-workers had on data-driven search and development and applied it to Queenly.

The search engine can go deeper than a normal dress search on Macy’s can, which might create options based on size, color and cut. In contrast, Queenly can help offer more diverse insights with a larger range of sizes, silhouette options and different shades of the same color.

Last week, a seller sold her wedding dress with a tag that says the dark mesh on the dress is for a darker skin tone. Queenly is beta-testing a feature that lets you search medium skin tone sheer options or dark skin tone sheer options. The team says that skin-tone filters are one of the important long-term goals of their search engine.

“These are just some things that we know because we’re women, and we know how to build this product for women,” Zhou said. “As opposed to if this was a male founder, they would not know that that would even be something that women would search for.”

Currently, there are over 50,000 dresses for sale on the Queenly platform, ranging from $70 to $4,000 and going up to size 32.

Image Credits: Queenly

With these search insights, Queenly says that it is able to sell dresses within two weeks, claiming that some users say that their same dresses spent five months on the Poshmark platform.

The diversity of dresses, from a price and range perspective, is one of the ways that Queenly stays competitive with large retail brands like Nordstrom.

“Buying and carrying inventory is very capital intensive for any startup,” Bantigue said. “As female minority founders it was hard for us to raise in the beginning.” As a result, the startup doesn’t keep a physical inventory of dresses, but instead relies on users to help get dresses from owner to buyer. If a dress is under $200, Queenly sends a prepaid shipping label to the seller to mail directly to the end buyer. If a dress is over $200, Queenly gets the dress sent directly to the company, does light dry cleaning and authentication, and then sends it right to the user.

Bringing the users into the transaction process adds a layer of risk because it depends on people to do things for the startup to be successful. The incentive here is that sellers make 80% of their sale price, and Queenly pockets the other 20%.

The startup’s biggest cost is shipping. To limit these costs, Queenly currently doesn’t accept or honor any returns, unless the dress upon arrival is not what was described in the sales post.

While this is a sensical business decision, it could be a hurdle for the startups’ clientele. Sizes are complicated and inconsistent, so the inability to return a dress might stifle a customer’s appetite to buy in the first place.

“We were actually worried about this before, but for two years now we [have not] had a complaint about sizing,” Bantigue said.

The co-founders say that many buyers are comfortable tailoring a dress post-purchase, and sellers are required to post pictures so expectations are set pre-purchase. There have been no cases of counterfeit brands to date, Bantigue said.

Queenly’s next plan is to bring on boutique stores and dress designers for Queenly partners, a program started to help small boutique businesses digitize their inventory through the Queenly platform.

“For years, the formalwear industry has been mostly offline, with only big name players being available online,” Bantigue said. “We want to change this.”